Frank Abagnale

Frank Abagnale | |

|---|---|

Abagnale in 2008 | |

| Born | Frank William Abagnale Jr. April 27, 1948 Bronxville, New York, U.S. |

| Citizenship | United States, France |

| Occupation | Secure document consultant |

| Criminal charge(s) | Auto larceny, theft, forgery, fraud |

| Criminal penalty |

|

Frank William Abagnale Jr. (/ˈæbəɡneɪl/; born April 27, 1948) is an American security consultant, author, and convicted felon who committed frauds that mainly targeted individuals and small businesses.[1][2][3] He later gained notoriety in the late 1970s by claiming a diverse range of workplace frauds,[4] many of which have since been placed in doubt by one author.[5][6] In 1980, Abagnale co-wrote his autobiography, Catch Me If You Can, which built a narrative around these claimed frauds. The book inspired the film of the same name directed by Steven Spielberg in 2002, in which Abagnale was portrayed by Leonardo DiCaprio. He has also written four other books. Abagnale runs Abagnale and Associates, a consulting firm.[7]

Abagnale claims to have worked as an assistant state attorney general in the U.S. state of Louisiana, served as a hospital physician in Georgia, and impersonated a Pan American World Airways pilot who logged over two million air miles by deadheading.[4] The veracity of most of Abagnale's claims has been questioned, and ongoing inquiries continue to confirm that they were fabricated.[8][9] In 2002, Abagnale admitted on his website that some facts had been overdramatized or exaggerated, though he was not specific about what was exaggerated or omitted about his life.[10] In 2020, journalist Alan C. Logan provided evidence he claims proves the majority of Abagnale's story was invented or at best exaggerated.[5][6] The public records obtained by Logan have since been independently verified by journalist Javier Leiva.[11]

Early life

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

Frank William Abagnale Jr. was born in the Bronx, New York City, on April 27, 1948, to an Algerian-American mother who died in November 2014, and an Italian-American father who died in March 1972.[13][14] He spent his early life in Bronxville, New York. His parents separated when he was 12 and divorced when he was 15 years old.[5] After the divorce, Abagnale moved with his father, and his new stepmother, to Mount Vernon, New York.[5]

Abagnale claims his first victim was his father, who gave him a gasoline credit card and a truck, and was ultimately liable for a bill amounting to $3,400. Abagnale was only 15 at the time.[15][16] In his autobiography, Abagnale says, because of this crime, he was sent to a reform school in Westchester County, New York (fitting the description of the Lincolndale Agricultural School) run by Catholic Charities USA.[15] In numerous interviews, Abagnale has claimed he attended an elite Catholic private school in Westchester, New York, Iona Preparatory School, through the 10th grade at age 16 in 1964.[12][17][18] Abagnale is not mentioned by name, though, nor do any photographs of him appear in the Iona Preparatory School yearbooks from the time he ostensibly attended. Moreover, no alumni recall Abagnale ever attending the high school.[5]

In December 1964, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy at the age of 16. He was discharged after less than three months, and was released on February 18, 1965.[5] Less than two weeks after his release, Abagnale was arrested for petty larceny in Mount Vernon on February 26, 1965.[19] The following month, in March 1965, Abagnale identified himself as a Scarsdale, New York, police officer and entered the apartment of a Mount Vernon, New York, resident claiming that he was investigating her teenaged daughter. Suspicious, the victim called the Mount Vernon police, who found Abagnale with a toy gun and a paper police badge. Abagnale was arrested and booked on a vagrancy charge after being identified in a lineup by the victim.[20] The following day, Abagnale was ordered by the court to be committed to Grasslands psychiatric institute, in Westchester County, for observation.[21]

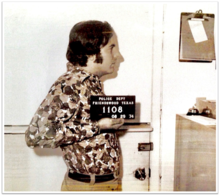

In June 1965, the Federal Bureau of Investigation arrested Abagnale in Eureka, California, for car theft after he stole a Ford Mustang from one of his father's neighbors. Abagnale was pictured in the local newspaper, seated in a car, being questioned by Special Agent Richard Miller of the FBI.[2] He had financed his cross-country trip from New York to California with blank checks stolen from a family business located on the Bronx River Parkway.[1][22] Abagnale was also charged with impersonating a US customs official, although this charge was subsequently dropped. On July 2, 1965, this stolen-car case was transferred to the Southern District of New York.[5]

Airline pilot

[edit]After being released into the custody of his father to face the stolen-car charges, 17-year-old Abagnale decided to impersonate a pilot. He obtained a uniform at a Manhattan uniform company, purchased with the money he obtained from the forgery of checks and on July 7, 1965, informed local media that he was a graduate of the American Airlines pilot school in Fort Worth, Texas,[23] but he was arrested for theft of checks in Tuckahoe, New York days later.[1][22] Abagnale was sentenced to three years at the Great Meadow Prison in Comstock, New York for these stolen checks. After serving only two years of his sentence, he was released into the custody of his mother, but he broke the terms of his parole with a stolen-car conviction in Boston, Massachusetts, and was returned to Great Meadow for one year.[5]

After his release on December 24, 1968, 20-year-old Abagnale disguised himself as a TWA pilot and moved to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where he talked his way into the house of a local music teacher, whose daughter was a Delta Air Lines stewardess he had met in New York. In Baton Rouge, Abagnale also befriended a local minister, claimed he had a master's degree in social work from Ithaca College, and sought work with vulnerable youth with intellectual and developmental disabilities.[24] The reverend introduced him to Louisiana State University faculty, who determined he was an "obvious phony".[25] The reverend, after Abagnale told him he was a furloughed TWA pilot, became suspicious and called the airline, which informed him that Abagnale was a fraud.[25] The reverend notified the Baton Rouge Police Department, and Abagnale was arrested on February 14, 1969, initially on vagrancy charges. Upon his arrest, he was found to have illegally driven his Florida rental car out of state and to possess falsified airline employee identification.[26] The following day, detectives determined that Abagnale had stolen blank checks from his host family and a local business in Baton Rouge, and he was subsequently charged with theft and forgery.[27][3] Unable to make bail, he was convicted on June 2, 1969, and was sentenced to 12 years of supervised probation, but he soon fled Louisiana for Europe.[5][28]

Europe

[edit]Two weeks after the Louisiana bench warrant was issued, Abagnale was arrested in Montpellier, France, in September 1969. He had stolen an automobile and defrauded two local families in Klippan, Sweden. He was sentenced to four months for theft in France, though he served only three months in Perpignan's prison.[29]

He was then extradited to Sweden, where he was convicted of gross fraud by forgery. He served two months in a Malmö prison, was banned from Sweden for eight years, and was required to compensate his Swedish victims (which he allegedly failed to do).[5] Abagnale was deported back to the United States in June 1970, when his appeal failed.[5]

United States

[edit]After returning to the United States, 22-year-old Abagnale dressed in a pilot's uniform and traveled around college campuses, passing bad checks and claiming he was there to recruit stewardesses for Pan Am. At the University of Arizona, he stated that he was a pilot and a doctor. According to Paul Holsen, a student at the time, Abagnale conducted physical examinations on several female college students who wanted to be part of flight crews.[30] None of the women were ever enrolled in Abagnale's fictional program, as his autobiography and film depict.[31]

After Abagnale cashed a personal check made to look like a Pan Am paycheck, on July 30, 1970, in Durham, North Carolina, he again came to the attention of the FBI. He was arrested in Cobb County, Georgia, three months later, on November 2, 1970, after cashing ten fake Pan Am payroll checks in different towns. Abagnale escaped from the Cobb County jail and was picked up four days later in New York City. He was sentenced to ten years in 1971 for forging checks that totaled $1,448.60 (equivalent to $11,225.45 in 2024),[32] and he received an additional two years for escaping from the local Cobb County jailhouse.[5][31]

In 1974, Abagnale was released on parole after he had served around two years of his 12-year sentence at Federal Correctional Institution in Petersburg, Virginia.[33] Unwilling to return to his family in New York, Abagnale says he left the choice of parole location up to the court, which decided that he would be paroled in Houston, Texas.[34]

After his release, Abagnale stated that he performed numerous jobs, including cook, grocer, and movie projectionist; he was fired from most of those after he was discovered to have been hired without revealing his criminal past. He again posed as a pilot in 1974 to obtain a job at Camp Manison, a summer children's camp in Texas, where he was arrested for stealing cameras from his co-workers.[35] After he received only a fine, he obtained a position at a Houston-area orphanage by pretending to be a pilot with a master's degree. This job had him finding foster homes for the children living at the orphanage. This ruse was eventually discovered by his parole officer, who swiftly removed him from his orphanage work and moved him into living quarters above his own garage, so he "could keep an eye on him".[36] His next position was at Aetna, where he was fired and sued for check fraud.[5]

According to Abagnale, he approached a bank with an offer in 1975. He explained to the bank what he had done and offered to speak to the bank's staff and show them various tricks that "paperhangers" use to defraud banks. His offer included the condition that if they did not find his information helpful, they would owe him nothing; otherwise, they would owe him only $50, with an agreement that they would provide his name to other banks.[37] With that, he began a new career as a speaker and security consultant.[7] During this time, he falsified his resume to show he had worked with the Los Angeles Police Department and Scotland Yard.[5]

In 1977, Abagnale gave public talks wherein he claimed that between the ages of 16 and 21, he was a pediatrician in a Georgia hospital for one year, an assistant state attorney general for one year, a sociology professor for two semesters, and a Pan American airlines pilot for two years. In addition, Abagnale claimed that he recruited female university students as Pan American flight attendants, traveling with them for three months throughout Europe. He also claimed he eluded the FBI with a daring escape from a commercial airline bathroom via the toilet bowl, while the plane was taxiing at the John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York.[38][39] In 1978, Abagnale told a Honolulu Advertiser reporter that he was familiar with the toilet apparatus, squeezed himself through the opening, swung down through the lower hatch, landed on the pavement, ran across the runway, and hailed a cab.[40] Abagnale claimed he moved the sewage container aside and that no one heard a thing: "I took off running. I thought they were right behind me. What I didn't know was that the door was spring loaded and when it slammed shut the whole assembly fell back into place. Nobody heard anything because of the engines' roar."[41]

He moved with his wife, Kelly, and their three sons to Tulsa, Oklahoma. He and his family lived in the same house for the next 25 years. After their sons left home for college and careers elsewhere, Kelly suggested that she and Frank leave Tulsa. They decided to move to Charleston, South Carolina.[34]

In 1976, he founded Abagnale & Associates,[7] which advises companies on secure documents. In 2015, Abagnale was named the AARP Fraud Watch Ambassador, where he helps "to provide online programs and community forums to educate consumers about ways to protect themselves from identity theft and cybercrime." In 2018, he began co-hosting the AARP podcast The Perfect Scam about scammers and how they operate.[42]

He has appeared in the media a variety of times, including three times as guest on The Tonight Show, an appearance on To Tell the Truth in 1977,[43][44][45] and a regular slot on the British network TV series The Secret Cabaret in the 1990s.[46] The book about Abagnale, Catch Me If You Can, was turned into a movie of the same name by Steven Spielberg in 2002, featuring actor Leonardo DiCaprio as Abagnale. The real Abagnale made a cameo appearance in this film playing a French police officer taking DiCaprio into custody.[47]

Veracity of claims

[edit]During his many speeches, appearances and interviews on television, Abagnale has alleged many criminal exploits.[48] These include stating that he was wanted in 26 countries, has worked extensively for the FBI, and escaped several times from FBI custody. He also claimed that he cashed over 17,000 bad checks, amounting to US$2.5 million, and worked as an assistant attorney general and a hospital physician. In addition, he stated that he started a fake stewardess trainee program, traveling with them throughout Europe for two months, and logged over three million air miles disguised as a pilot.[5] Almost all of these claims have been refuted by journalists.[9][11][31][48][49]

In public lectures describing his life story, Abagnale has consistently maintained that he was "arrested just once," and that was in Montpellier, France.[50][51] However, public records show Abagnale was arrested in New York (multiple times), California, Massachusetts, Louisiana, Georgia, and Texas.[1][28][29][52]

Despite public records showing Abagnale targeted individuals and small family businesses,[2][3][35][53] Abagnale has long claimed publicly that he "never, ever ripped off any individuals."[54] He made the same claim of never targeting individuals and small businesses to BBC journalist Sarah Montague and the Associated Press.[55][56] According to Abagnale, the only individual he ever swindled was a Miami prostitute: "She tried to charge me $1,000 for an evening, so I gave her a $1,400 forged cashier's check, and got $400 in change."[57] In 2002, Abagnale told the Star Tribune, "As long as I didn't hurt anyone, people never considered me a real criminal, my victims were big corporations. I was a kid ripping off the establishment."[58]

Individuals criminally targeted by Abagnale, however, have described the long-term consequences of victimization:[3]

He had a key to our front door, it was never recovered. We changed the lock. I fed him. I cooked. I don't trust people as much anymore.

— Charolette Parks, Abagnale victim interviewed April 27, 1981, The Advocate

His claim that he passed the Louisiana bar examination, worked for Attorney General Jack P. F. Gremillion, and closed 33 cases, was challenged by several journalists in 1978.[31][48] No record has been found of Abagnale ever being a member of the Louisiana Bar,[59] and no evidence shows he ever worked as an assistant attorney general in Louisiana's Attorney General's Office. In 1978, the Louisiana State Bar Association reconciled all those who took the bar exam and concluded that Abagnale never took the exam using his own name or an alias; the State Attorney General's Office examined payments to all employees during the time Abagnale claimed he worked there and concluded that he never worked in the office using his name or an alias.[31] After Abagnale appeared on The Tonight Show, then-First Assistant Attorney General Ken DeJean gave a reporter a series of questions to ask Abagnale about the description of then-Attorney General Gremillion. Abagnale failed to answer the questions correctly.

The man is not an imposter, he is a liar.

— Kenneth C. DeJean, First Assistant Attorney General, 'The Great Imposter', April 24, 1981, The Advocate[49]

Abagnale claimed that when he was 18 years old, he worked for a year as a supervising pediatrician at the Cobb General Hospital in Marietta, Georgia. He maintained that he worked the midnight-to-8 am shift, supervising seven residents and 42 nurses.[31] Abagnale claimed that he would visit the university library to memorize medical journals and textbooks: "With my photographic memory, I could easily memorize anything. That did not mean that I could comprehend it, but I could rattle it off verbatim."[60] Abagnale told his audiences that over the course of his one year at Cobb General, no one doubted his position as a physician: "So I made the rounds, picked up the clipboards, scribbled a few lines, initialed them, and everyone thought I was doing a fine job."[61] However, hospital administrators told journalist Ira Perry that the hospital had no midnight-to-8 am shift, nor did the position of regular overnight pediatrician exist, at the time.[31] Using records from the New York State Archives, author Alan C. Logan demonstrated that Abagnale was in the Great Meadow Prison, in Comstock, New York, when he was 18.[5]

Abagnale's claim that he impersonated a doctor is not entirely without foundation, however. On the University of Arizona campus in 1970, he stated that he was a pilot and a doctor. According to Paul Holsen, who was an older university student and licensed commercial pilot at the time,[62] Abagnale informed him that he was there on behalf of Pan Am to recruit and conduct physical examinations on candidates. In his autobiography, Holsen claimed that after Abagnale's ruse was discovered, authorities informed him that Abagnale had indeed conducted physical exams on students.[30] University of Arizona officials acknowledge that Abagnale had interacted with 12 female students.[31] Abagnale has openly acknowledged that he performed examinations on young women while impersonating a doctor: "When the girls came by, I always gave them a thorough examination and sent them on their way. I was young, but not stupid."[63][64][65] In 2021, Louisiana State University Manship Chair in Journalism Robert Mann expressed his regret in not confronting Abagnale's claim of conducting physical examinations as a doctor: "Looking back on my story about the event [Abagnale's lecture], I am embarrassed by what I wrote about Abagnale's time posing as a pediatrician. Reading those words now, in which Abagnale bragged about sexual abuse, makes me sick."[66]

Abagnale has publicly claimed an intelligence quotient (IQ) of 140: "I have an I.Q. of 140 and retain 90% of what I read. So, by studying and memorizing the bar exam, I was able to get the needed score."[39] In 2021, Abagnale gave the keynote speech at the American Mensa Conference in Houston. The organizers claimed he was the subject of an FBI manhunt and cashed millions of dollars' worth of checks while impersonating a pilot and doctor.[67] Despite claims of a photographic memory, when queried by USA Today journalist Andy Seiler regarding details of his imposter roles and movements in the 1960s, Abagnale responded by saying, "You get to a point in your life where you go, 'I don't remember what I did.'"[68]

One of Abagnale's most notable claims was an alleged escape from the United States Penitentiary, Atlanta, in 1971:[69]

I was in one of the largest maximum-security federal prisons for two weeks when I impersonated a prison inspector and walked out, right past the machine guns and the guards.

— Frank W. Abagnale, Ex-con tells tricks of trade, El Paso Herald-Post

In 1982, Abagnale told the press, "I was and still am the only and youngest man to escape from that prison."[60] The Federal Bureau of Prisons confirmed, though, that Abagnale was never housed in the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary: "He was never admitted, so I don't really see how he could have escaped," said acting Warden Dwight Amstutz.[31]

In 1978, after Abagnale had been a featured speaker at an anticrime seminar, a San Francisco Chronicle reporter looked into his assertions. Telephone calls to banks, schools, hospitals, and other institutions Abagnale mentioned turned up no evidence of his cons under the aliases he used. Abagnale's response was, "Due to the embarrassment involved, I doubt if anyone would confirm the information." He later said he had changed the names.[70]

Further doubts were raised about Abagnale's story after an October 1978 appearance on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, with a news article saying:

Abagnale is indeed a convicted confidence artist. But he is finding willing believers as he promotes and invents a more varied criminal past.

— Stephen Hall, San Francisco Chronicle, 'Johnny is conned' October 6, 1978.[71]

In December 1978, Abagnale's claims were again investigated after he visited Oklahoma City for a talk.[31] As part of his investigation into the story, Perry spoke with Pan Am spokesman Bruce Haxthausen, who responded to the journalists' inquiry saying:

This is the first we've heard of this, and we would have heard of or at least remember[ed] it if it had happened. You don't forget $2.5 million in bad checks. I'd say this guy is as phony as a $3 bill.

— Ira Perry, The Daily Oklahoman, Inquiry Shows 'Reformed' Con Man Hasn't Quit Yet, December 10, 1978

In 2002, Abagnale addressed the issue of his story's lack of truthfulness with a statement posted on his company's website, which said in part: "I was interviewed by the co-writer only about four times. I believe he did a great job of telling the story, but he also overdramatized and exaggerated some of the story. That was his style and what the editor wanted. He always reminded me that he was just telling a story and not writing my biography."[72] However, Abagnale made the primary claims of working as a doctor for a year, an attorney for a year, a PhD professor, and his several escapes on national television in 1977 on the show To Tell the Truth and The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson,[45][73] which antedated the 1980 autobiography by several years. He also made these claims in print media, namely the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, three years before the publication of his co-written autobiography, effectively nullifying the claim his aforementioned co-author, Stan Redding, exaggerated the story.[39]

Despite Abagnale's website claim about his autobiography co-author Stan Redding, investigative journalist Javier Leiva discovered an obscure cover story of True Detective (January 1978) in which Abagnale told the story of his life. In True Detective, Abagnale claimed to Redding that he passed the Louisiana bar exam, worked as an assistant attorney general, was employed as a sociology professor, worked as an Atlanta pediatrician, escaped from an airplane toilet, escaped from the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary, recruited University of Arizona students (and traveled with them throughout Europe for weeks), and cashed $2.5 million in checks. These claims antedate, by several years, the co-authored autobiography, and they also demonstrate that it was Abagnale who invented and exaggerated his life story, not Stan Redding.[74]

In 2002, at the Catch Me If You Can film premiere, Abagnale conceded to journalist Andy Seiler of USA Today that the impersonations in the autobiography were fabricated: "I impersonated a doctor for a few days, I was a lawyer for a few days. In the book, it's like I am doing this for a year."[68] Despite this admission, in public speeches, Abagnale would return to his claims of long-term impersonations of a doctor and for working for a year as an attorney.[12][50][51] Abagnale's fees for speaking about his alleged life story are reported to be between $20,000 and $30,000.[8]

In 2006, KSL journalist Scott Haws challenged Abagnale with his claim that he worked as a PhD-holding sociology professor at Brigham Young University (BYU) for two semesters. Abagnale claimed that he could not recall the details, and that his co-author Redding had exaggerated some things. Haws "refreshed Frank's memory" and showed him his own words, including the Catch Me If You Can movie book and the credits that rolled at the end of the film Catch Me If You Can, where Abagnale, not Redding, made the BYU professor claim.[75] Abagnale conceded to Haws that he might have been a guest lecturer.[76]

So despite claiming to be a sociology professor in at least three books, two solely written by Abagnale himself, and an on-camera claim following the movie, it appears Abagnale as a BYU professor is mostly or entirely just another real fake.

Leading up to 2020, author Alan C. Logan conducted an in-depth investigation for a book that focused on the perspective of Abagnale's victims. As part of this process, Logan combined earlier newspaper articles, numerous administrative documents, and public records that had not been the subject of scrutiny by major media outlets. Based on these documents, Logan provided a timeline that challenged the overall truthfulness of Abagnale's self-described criminal history and movements between 1964 and 1974.[5] Logan maintains that his investigation found that Abagnale's account of his criminal past is, for the most part, a fabrication. Using records from the New York State Archives, Logan showed that Abagnale was in Great Meadow Prison in Comstock, New York, between the ages of 17 and 20 (July 26, 1965, and December 24, 1968) as inmate #25367, the time frame during which Abagnale claims to have committed his most significant scams. Logan's investigation uncovered numerous petty crimes that Abagnale has never acknowledged.[6] Various media outlets have asked Abagnale to respond to Logan's book content, which included victim statements and citations to publicly accessible records. Abagnale has responded by stating that the book is "not worthy of a comment".[6][8]

Abagnale has told the press, "I was convicted on $2.5 million dollars' worth of bad checks" and that he later hired a law firm to get all the money back to hotels and other companies.[77] Federal court records, though, show that Abagnale was convicted of forging 10 Pan American Airlines checks in five states (Texas, Arizona, Utah, California. and North Carolina), totaling less than US$1,500.[5] Following his parole on February 8, 1974, he claimed he went to work for the FBI, but after this date, Abagnale was arrested for theft at a kids' camp in Friendswood, Texas, on August 29, 1974.[35]

In many interviews and speeches, Abagnale has claimed that he has earned millions of dollars from his patents.[50][78] The United States Patent and Trademark Office website, to the contrary, does not list Abagnale—as a person—or Abagnale and Associates—as a business—as holders of any patents, and neither are listed as an inventor on any patent.[79] In his cheque design patents, Canadian inventor Calin A. Sandru merely mentions in the Background section of the invention that KPMG and Abagnale and Associates are groups that affirm that cheque fraud is a significant problem.[80][81][82]

Logan, girded with public records, shared his findings in detail on the NPR program Watching America, August 13, 2021, broadcast on WHRO.[83]

In 2022, investigative journalist Javier Leiva independently obtained the public records first sourced by Logan. Leiva also confirmed that Abagnale was in prison between 17 and 20 and then convicted for theft in Baton Rouge in June 1969. Leiva also obtained the federal records connected to Abagnale's Pan Am checks and confirmed that his conviction, at 22 years old, was based on less than $1,500. Leiva says he calculated that between 1965 and 1970, Abagnale was only free for a matter of months and that his records show he was in prison most of that time. On June 23, 2022, Leiva confronted Abagnale at the Connect IT Global 2022 conference in Las Vegas with prison and other public records in-hand. Leiva describes these events in his podcast series Pretend – The Real Catch Me If You Can (Part 1).[11]

Relationship with the Federal Bureau of Investigation

[edit]One of Abagnale's most controversial claims is his relationship with the FBI. In 1977, when Abagnale began claiming a five-year uninterrupted life on the run, involving multiprofession imposter scams, he did not claim to work for the FBI. He did, however, leverage the names of FBI personnel to bolster his new biographical claims. In 1978, journalist Ira Perry determined that Abagnale and his publicist were giving out the names of FBI agents to any party that asked for references or verification of his claimed biography; in particular, they gave out the name of Robert Russ Franck, who they claimed was the "former Atlanta agent" who knew all about Abagnale.[31] When Perry contacted Franck, who had just retired as head of the FBI's Houston Division, and had never worked in Atlanta, Franck told him:

That damn Abagnale uses my name all over the place, but I've never even met the guy.

— Robert Russ Franck, The Daily Oklahoman, "Inquiry Shows 'Reformed' Con Man Hasn't Quit Yet", December 14, 1978[31]

Franck informed Perry that he had only heard about Abagnale through people attempting to verify his biographical claims, and was unable to confirm whether the claims were true. Perry also interviewed Eugene Stewart, a retired FBI agent who was in charge of the Atlanta division when Abagnale claimed he was a pediatrician in suburban Atlanta. Stewart, who at this point was Delta Air Lines chief of security, informed Perry that Abagnale was a low-level criminal: "It's more of a harassment than anything else," said Stewart. In addition, Stewart noted that Abagnale had been using a Delta Air Lines uniform to cash bad personal checks in Texas after his 1974 parole.[31] After his parole, Abagnale was arrested for theft from a children’s camp in Friendswood, Texas.[35] Public records show that almost two years after his parole, in October 1975, Abagnale was hired by Aetna Insurance, and was abruptly fired by the company after he allegedly cashed bad personal checks during his employee training. Aetna eventually filed suit against Abagnale after his appearance on To Tell the Truth was broadcast in 1977.[5]

After the publication of his 1980 autobiography, Abagnale began to inform his audiences that he was on the FBI Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list.[84] He carried this claim into the '90s: "I was the only teenager in the history of the FBI to be put on their 10 Most Wanted list," Abagnale told his audiences in 1994.[85] In the lead up to the release of the film Catch Me If You Can, this "Ten Most Wanted Fugitives" claim was used in marketing for the film.[86] Pressed on this claim when the film was released, and with evidence clearly showing the absence of Abagnale on any most wanted list,[87] he conceded on his website that he was never on the FBI's Most Wanted list.[88][89]

In 2002, Los Angeles Times journalist Bob Baker (1948–2015) reported that no FBI task force was set up to capture Abagnale.[90] Despite his claims that he was living in the infamous Riverbend Apartments, supposedly eluding the FBI for one year as a pediatrician in suburban Atlanta, the newspaper report of Abagnale's arrest indicated he had been in the area for only two days; local FBI agents responded to a tip that Abagnale was in a local hotel and arrested him there.[91] In September 2022, retired FBI Agent Alan Brown obtained permission from FBI headquarters to discuss his arrest of Abagnale. Brown spoke to investigative journalist Javier Leiva and acknowledged that the Atlanta field office simply acted on a teletype request to pick Abagnale up at the Squire Inn, in Marietta, Georgia. In contrast to Abagnale's claims about escaping from the hotel,[92] as depicted in the film, Brown stated that Abagnale was arrested in his room without incident. Brown also stated that he had no personal knowledge of Abagnale's arrests prior to 1970, and after 1970, when Abagnale was arrested in Friendswood, Texas.[93]

In the years following the release of Catch Me if You Can, Abagnale began claiming that he was granted a unique parole from the federal prison in Petersburg, Virginia, so that he could work for the bureau: "When the FBI took me out of prison, it was to do undercover work."[94] Abagnale has claimed that the clandestine work was given to him directly by Clarence M. Kelley, who directed the FBI from 1973 to 1978. In his "Talks at Google" lecture, Abagnale claimed that because of his photographic memory, Kelley asked him to memorize the components of military hardware and infiltrate bases as a lieutenant. Abagnale describes Kelley's instructions this way: "Okay, you are a lieutenant in the army. You have been in the army this many years. Your expertise is this missile. I need you to learn all of this in two weeks, and I'm sending you to this base, and I want you to find out what's going on in this particular area." In the lecture, Abagnale also claims Kelley sent him on similar missions "as a scientist at a lab in New Mexico."[51]

Jerri Williams, a retired FBI agent who specialized in white-collar crime and fraud, spoke to investigative journalist Javier Leiva about these claims. Williams rejected Abagnale's claims of being tasked with clandestine operations directly by Kelley:

If anybody tells you that they got an assignment directly from the FBI director, right from the head of the FBI, you know for a fact it's bullshit. It doesn't happen that way.

— Jerri Williams, Retired FBI Agent, Pretend Radio, Episode 05[95]

After the film was released, Abagnale began to use the first-person plural pronoun "we" to refer to the FBI;[51] he also began to inform audiences that he was directly working for the FBI and celebrating each anniversary of his unique parole and the opportunity to go to work at the FBI; for example, in 2006, he informed his audiences, "This year I am celebrating 31 years with the FBI,"[50] in 2014, he told his audiences, "this year I'm celebrating 38 years at the FBI where I work today."[96] The dates of this anniversary celebration point to 1976 and do not line up with Abagnale's claim of a parole-release deal. Abagnale was, according to United States Board of Parole and Federal Bureau of Prisons standard practice at the time, sent to a pre-release center in Houston in 1973, within the 120 days prior to his actual federal parole date of February 8, 1974.[5][31]

Ira Winkler, former intelligence analyst for the United States Department of Defense, and chief security architect for Walmart stores internationally,[97] describes an encounter with Abagnale. Winkler queried Abagnale on the specifics of his position at the FBI. Abagnale responded that he was, "a special agent". Winkler says, "You mean a full-fledged special agent?", to which Abagnale responded in the affirmative.[98]

In a 2018 interview broadcast on PBS, Abagnale publicly criticized former FBI director James Comey for his unprofessionalism during the 2016 US presidential election. In the same interview, Abagnale claims that the FBI is concerned that he is of retirement age: "The FBI always ask me when am I going to retire, because they don't want me to," said Abagnale.[99] In interviews, Abagnale has claimed that his work with the FBI is pro bono, although he has claimed publicly that his company has made millions of dollars from contracts with the U.S. government: "Today, Frank Abagnale and Associates does $10.5 million of business per year, 90% of it with the federal government," he told his audience in 1988.[100] In 1991, Frank Abagnale and his wife Kelly filed for bankruptcy in Tulsa, Oklahoma. In the court filings, Abagnale claimed that he had $1.6 million in debts and $308,000 in assets.[101]

Journalist Ira Perry was unable to find any evidence that Abagnale worked with the FBI; according to one retired FBI special agent in charge, Abagnale was caught trying to pass personal checks in 1978 several years after he claimed that he began working with the FBI.[31] Dating back to the 1980s, Abagnale claimed that Joseph Shea, an FBI agent, had pursued him for five years (between 1965 and 1970).[102] Abagnale claimed that Shea befriended and supervised him during his parole.[5] When Catch Me If You Can was released in theatres, though, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported that Abagnale and Shea only reunited in the late 1980s, almost 20 years after Shea arrested him. Abagnale spotted Shea at an anticrime seminar in Kansas City and sought out Shea to shake his hand.[103]

When the film was released, an FBI spokesperson acknowledged that Abagnale had given lectures at the academy "from time to time," but denied that Abagnale had been given commendations by the agency as claimed in the film's marketing.[104] At no point has the FBI made an official statement corroborating Abagnale's biographical claims, nor has the agency confirmed his extraordinary claims that he was sent into a military base as an expert on missiles, and into a secret lab in New Mexico.[51][105] Abagnale has claimed in public lectures that he was discussed in detail in a coffee-table book celebrating 100 years of the FBI.[51] However, Abagnale's name does not appear anywhere in the official book celebrating 100 years of the FBI.[106] In his public lectures, Abagnale has taken on a pseudo-spokesperson role for the FBI. In discussing recruitments, he states, "currently [2017] we take 1 in 10,000 applications."[51] Abagnale made this same claim of 1 in 10,000 applications to Idaho Statesman journalist Michael Katz in 2019.[107] Overall approximately 11,500 applications per year are made for 900 positions at the FBI (2018 statistics), which is about one in 13 applicants.[108]

In 2020, Abagnale was confronted by one of his victims in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. When asked why he talks about being an attorney general and passing the state's bar exam, and yet failing to acknowledge his arrest and conviction in Baton Rouge, Abagnale said, "That's because I work for the FBI."[28] Abagnale claimed to the Star Tribune that he is an ethics instructor at the FBI Academy in Quantico, Virginia: "I teach ethics at the FBI academy, which is ironic, but years ago, someone at the bureau said, 'Who better than you to do this?'—I try to teach young agents the importance of doing the right thing."[109]

Talks at Google

[edit]In August 2022, Google disabled all comments and added a disclaimer to Abagnale's "Talks at Google", which now states: "Disclaimer: Google does not endorse or condone the content contained within this video, nor does it lay claim to the validity of the actions described herein. The following is presented unaltered as it was recorded on Nov 27, 2017, and remains on the Talks at Google YouTube channel for historical purposes."[51][17] In the video disclaimer Google did not provide an explicit reason for the abnegation of Abagnale's video or whether or not it was part of their new initiative to work with journalists to combat misinformation and disinformation.[110] However, according to investigative journalist Javier Leiva, the move was made in response to members of his audience.[74]

Controversy at Xavier and other universities

[edit]On September 12, 2022, Frank Abagnale was awarded the "Heroes in Ethics" award by Xavier University, located in Cincinnati, Ohio. Abagnale gave the keynote lecture at the university's annual Heroes of Professional Ethics series. At the conclusion of his talk, Abagnale invited the audience to ask him any questions on any matter. A member of the audience, Jim Grinstead, the host of the podcast Scams and Cons,[111] asked Abagnale, “So I wonder, in light of the ethics award you’re going to be presented tonight, would you come clean? Would you tell the truth about the stories you’ve told? Will you admit that you just lied to everybody, and you’re still conning them?” In his response Abagnale denied telling any lies or spreading any misinformation. He claimed he had nothing to do with his autobiography, the film, and the Broadway musical.[74] Xavier University has removed any discussion of the September 12 event from its website.[112]

The incident at Xavier University was not the first time Abagnale's story caused controversy on a university campus. In 1981, after criminal-justice professor William Toney and his students debunked Abagnale's biographical claims, several universities cancelled Abagnale's appearances. In an attempt to provide compromise, the University of South Carolina asked Abagnale to sign an affidavit that would attest to the truthfulness of his biographical claims. The university informed Abagnale that he would still be allowed to give the speech and collect his speaking fee, even if he did not sign the affidavit, but if he refused, the university would warn the students at the outset of the speech that Abagnale had not promised to tell the truth. Abagnale refused to sign the affidavit, referring to the document as a "slap in the face".[113]

As skepticism of Abagnale's story spread, he cancelled his own university bookings. In a letter to Georgia Southwestern State University, Abagnale wrote that it was wrong to profit from his criminal past by speaking about it to college campuses. Furthermore, in the letter to GSSU, Abagnale stated that he was cancelling all college speaking engagements because the criminal aspects of the life story he was presenting "[are] not something to which young impressionable minds should be exposed."[114] In the midst of this controversy, Abagnale was queried by journalist John Dagley, who asked him if his biography was a lie, to which he replied:[113]

"Well, then, I am the world's greatest con man. As one gentleman said to me, 'If you didn't do all those things, and you've made all this money you've made in advances, royalties, and speaking engagements, then you are in fact the world's greatest con man.'"

— Frank W. Abagnale, "Con Man Under Fire" p. 2, Ledger-Enquirer, 1981, commenting on if his autobiography was fabricated.

Personal life

[edit]Abagnale and his wife Kelly live on Daniel Island, an island community which is part of Charleston, South Carolina. They have three sons, Scott, Chris, and Sean.[115] Abagnale maintains that meeting his wife was the motivation for changing his life. He told author Paul Stenning that he met her while allegedly working undercover for the FBI when she was a cashier at a grocery store.[5][116]

Books

[edit]- The Greatest Hoax on Earth: Catching Truth, While We Can, Alan C. Logan, 2020 ISBN 978-1-7361-9741-7

- Catch Me If You Can, 1980. ISBN 978-0-7679-0538-1

- The Art of the Steal, Broadway Books, 2001. ISBN 978-0-7679-0683-8

- Real U Guide to Identity Theft, 2004. ISBN 978-1-932999-01-3

- Stealing Your Life, Random House/Broadway Books, 2007. ISBN 978-0-7679-2586-0

- Scam Me If You Can, 2019. ISBN 978-0-5255-3896-7

See also

[edit]- The Great Impostor, 1961 movie about Ferdinand Waldo Demara

- Elliot Castro, Scottish former fraudster

- William Douglas Street Jr., American con artist and impersonator upon whose life the 1989 film Chameleon Street, winner of the Grand Jury Prize at the 1990 Sundance Film Festival, was based

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Clipped From The Herald Statesman". The Herald Statesman. July 16, 1965. p. 26. Archived from the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Abagnale Arrested for Auto Theft". Eureka Humboldt Standard. June 22, 1965. p. 11. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "BR Family Says Renowned Imposter Took Its Money". The State Times Advocate. April 27, 1981. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ a b "Abagnale's First Lecture With New Biography". The Galveston Daily News. January 25, 1977. p. 1. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Logan, Alan C. (2020). The Greatest Hoax on Earth: Catching Truth, While We Can. Indiana Landmarks. ISBN 9781736197417. OCLC 1253312173.

- ^ a b c d Lopez, Zavier (April 23, 2021). "Could this famous con man be lying about his story? A new book suggests he is". WHYY-TV. Archived from the original on February 8, 2022. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Abagnale & Associates". Abagnale & Associates. Archived from the original on January 17, 1999. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ^ a b c Stringfellow, Jonathan; DeMarco-Jacobson, Jessica (June 24, 2021). "Infamous American Fraudster Frank Abagnale to speak at upcoming CSU event". The Uproar. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ a b McNeilly, Claire (July 2, 2021). "Northern Ireland man exposes 'Catch Me If You Can' as work of fiction". Belfast Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on November 13, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ Baker, Bob (December 28, 2002). "The truth? Just try to catch it if you can". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 13, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c "The Real Catch Me If You Can (part 1)". Pretend Podcast. July 6, 2022. Archived from the original on July 21, 2022. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Catch Me If You Can: Frank Abagnale's Story". WGBH Educational Foundation. Archived from the original on July 25, 2022. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

- ^ "Paulette Noel Abagnale, 87, Of Mamaroneck". Mamaroneck Daily Voice. November 18, 2014. Archived from the original on August 28, 2022. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ^ "Obituary for Frank W. Abagnale". Daily News. March 14, 1972. p. 95. Archived from the original on August 28, 2022. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ^ a b Abagnale, Frank (2000). Catch Me If You Can. New York City: Broadway Paperbacks. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-7679-0538-1.

- ^ Bell, Rachael. "Skywayman: The Story of Frank W. Abagnale Jr". TruTV Crime Library. Atlanta, Georgia: Turner Broadcasting Systems. Archived from the original on August 31, 2009.

- ^ a b Frank Abagnale | Catch Me If You Can | Talks at Google, archived from the original on February 6, 2021, retrieved August 28, 2022

- ^ Frank Abagnale – FedTalks 2013, June 20, 2013, archived from the original on November 16, 2022, retrieved November 16, 2022

- ^ "Abagnale charged with petit larceny". The Daily Argus. February 27, 1965. p. 5. Archived from the original on December 13, 2022. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- ^ "Abagnale impersonates police office with toy gun and paper badge". The Daily Argus. March 12, 1965. p. 12. Archived from the original on December 13, 2022. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- ^ "Abagnale committed to Grasslands psychiatric hospital for observation". The Daily Argus. March 13, 1965. p. 11. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- ^ a b "Clipped From The Daily Times". The Daily Times. July 16, 1965. p. 2. Archived from the original on July 18, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ "Abagnale claims to graduate pilot school". The Daily Argus. July 7, 1965. p. 26. Archived from the original on December 13, 2022. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- ^ Anon (February 14, 1969). "Man with false co-pilot card held here". The Advocate (Louisiana). p. 9-A. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ a b Tomkins, Fayette (April 27, 1981). "BR Family". The Advocate (Louisiana). p. 9-B. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ "Vagrancy Charged Filed in City Against 'Pilot'". The Advocate. February 15, 1969. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ "N.Y. Man Faces 2 Counts Here". The State Times Advocate. February 15, 1969. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Did LABI pay a five-figure fee to get flim-flammed by self-proclaimed flim-flam artist at its annual luncheon Tuesday?". Louisiana Voice. February 13, 2020. Archived from the original on October 1, 2020. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Logan, Alan (2020). The Greatest Hoax on Earth Catching Truth, While We Can. Alan C. Logan. pp. 147–155. ISBN 9781736197400.

- ^ a b Holsen, Paul; Holsen II, Paul J. (2014). Born in a Bottle of Beer. Createspace Independent Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5003-8278-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Clipped From The Daily Oklahoman". The Daily Oklahoman. December 14, 1978. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 5, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ "CPI Inflation Calculator". data.bls.gov. Retrieved August 16, 2024.

- ^ Conway, Allan (2004). Analyze This: What Handwriting Reveals (1st ed.). PRC Publishing. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-85648-707-8.

- ^ a b Eaton, Kristi; Holton Dean, Anna (March 2019). "The Road to Fame: Frank Abagnale". Tulsa People. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Clipped From The News". The News. September 5, 1974. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ "Uncovering the Con Man's Biggest Lie". Archived from the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ Abagnale, Frank W. (2001). The Art of the Steal. Broadway Books. ISBN 9780767910910.[page needed]

- ^ "Abagnale Makes Biographical Claims". Plano Daily Star-Courier. February 11, 1977. p. 8. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Clipped From Fort Worth Star-Telegram". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. November 9, 1977. p. 20. Archived from the original on September 5, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ "Abagnale Claims Toilet Bowl Escape". Newspapers.com. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ "The Great Imposter Biographical Claims". The Times. February 21, 1982. p. 95. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ "Fraud Watch Ambassador Named". August 27, 2015. Archived from the original on August 28, 2015. Retrieved August 25, 2019.

- ^ List of The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson episodes (1978)

- ^ "The Tonight Show". December 3, 2013. Archived from the original on May 17, 2014. Retrieved May 16, 2014.

- ^ a b Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: To Tell The Truth (Joe Garagiola) (Imposter Frank Abagnale) (1977), retrieved July 25, 2021

- ^ Production company website Archived October 18, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, accessed April 19, 2021.

- ^ Van Luling, Todd (October 17, 2014). "11 Easter Eggs You Never Noticed in Your Favorite Movies". HuffPost. TheHuffingtonPost.com, Inc. Archived from the original on October 18, 2014. Retrieved January 29, 2015.

- ^ a b c Hall, Stephen (October 6, 1978). "Johnny Is Conned". No. 114th Year, No. 221. San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ a b Tompkins, Fayette (April 24, 1981). "Is great imposter a great imposter?". The Advocate. pp. 1B, 7C. Archived from the original on March 14, 2024. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "American Rhetoric: Frank Abagnale – National Automobile Dealers Association Convention Address". www.americanrhetoric.com. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Talks at Google: Ep1 – Frank Abagnale | Catch Me If You Can". talksatgoogle.libsyn.com. Archived from the original on October 27, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ "Abagnale interacts with coeds using deception". Arizona Daily Star. November 21, 1970. p. 34. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ "BR Family Says Renowned Imposter Took Its Money". State Times Advocate. April 27, 1981. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ "Frank Abagnale claimed he never ripped off any individuals". The Item. September 29, 1982. p. 5. Archived from the original on September 17, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: BBC HardTalk Interview with Frank Abagnale, retrieved September 17, 2021

- ^ "Frank Abagnale claimed he never targeted 'mom and pop' stores". The Ithaca Journal. November 20, 1980. p. 29. Archived from the original on September 17, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ "Abagnale Describes Stealing from Call Girl". El Paso Times. October 20, 1977. p. 11. Archived from the original on May 10, 2022. Retrieved March 13, 2022.

- ^ "Abagnale Claims Never Considered Real Criminal". Star Tribune. December 22, 2002. p. F7. Archived from the original on October 15, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ "Attorney Status Search". ladb.org. Archived from the original on July 29, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ a b "Abagnale Claims Escape From Atlanta Federal Penitentiary". Arizona Daily Sun. February 24, 1982. p. 6. Archived from the original on September 5, 2022. Retrieved September 21, 2021.

- ^ "Abagnale Describes Work as a Pediatrician". The Tampa Tribune. March 26, 1981. p. 161. Archived from the original on April 29, 2022. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ "Alumni Reflections". Arizona Alumni Association. August 14, 2013. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved March 13, 2022.

- ^ "Abagnale Describes Physical Exams". The Daily Herald. March 11, 2005. p. 32. Archived from the original on May 10, 2022. Retrieved March 13, 2022.

- ^ Botes, Zanandi (April 16, 2022). "'Catch Me If You Can' – The Real Guy Was Full Of It". Cracked.com. Archived from the original on May 10, 2022. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- ^ "Ohio State catches Frank Abagnale for lecture on life, time in FBI". The Lantern. February 26, 2014. Archived from the original on April 29, 2022. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- ^ Mann, Robert (2021). Backrooms and bayous : my life in Louisiana politics. New Orleans. ISBN 978-1-4556-2597-0. OCLC 1224584079.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "American Mensa's World Gathering | Aug. 24–29, 2021". ag.us.mensa.org. Archived from the original on September 21, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2021.

- ^ a b "Abagnale Can't Remember". Wausau Daily Herald. December 29, 2002. p. 36. Archived from the original on April 29, 2022. Retrieved March 13, 2022.

- ^ "Abagnale claims prison escape". El Paso Herald-Post. February 22, 1979. p. 25. Archived from the original on April 29, 2022. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ^ Baker, Bob (December 6, 2002). "Portrait of the con artist as a young man". newsthinking.com. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- ^ Hall, Stephen (October 6, 1978). "Johnny Is Conned". No. 114th Year, No. 221. San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ "Abagnale & Associates, Comments". Archived from the original on February 16, 2009. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

- ^ Frank Abagnale Stuns Everyone With Stories of Being a Con Man | Carson Tonight Show, archived from the original on July 22, 2022, retrieved July 22, 2022

- ^ a b c "Frank Abagnale, a conman, gets an ethics award (part 8)". Pretend Podcast. October 11, 2022. Archived from the original on October 11, 2022. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- ^ Steven Spielberg; Frank W. Abagnale; Andrew Cooper; Jeff Nathanson; Timothy Shaner (2002). Linda Sunshine (ed.). Catch Me If You Can: A Steven Spielberg Film. New York: Newmarket Press. ISBN 1-55704-553-4. OCLC 51995375.

- ^ "Did Frank Abignale Really Teach at BYU?". www.ksl.com. April 27, 2006. Archived from the original on July 20, 2021. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ "Charleston Home + Design Magazine – Spring 2014". Issuu. March 25, 2014. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ "The art of the steal". The Daily Universe. March 11, 2005. Archived from the original on October 31, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ "Patent Database Search Results: abagnale in US Patent Collection". patft.uspto.gov. Retrieved October 31, 2021.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Sandru, Calin A. (February 28, 1997). "Apparatus and method for enhancing the security of negotiable documents". United States Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved October 31, 2021.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Sandru, Calin A. (May 4, 2000). "Apparatus and method for enhancing the security of negotiable documents". United States Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved October 31, 2021.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Sandru, Calin A. (July 1, 2002). "Apparatus and method for enhancing the security of negotiable instruments". United States Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved October 31, 2021.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "WHRO Radio & TV Programs, Podcasts, Episodes". WHRO. Archived from the original on August 21, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ "Abagnale Claimes [sic] FBI Most Wanted". The Post-Crescent. October 18, 1980. p. 3. Archived from the original on April 30, 2022. Retrieved April 30, 2022.

- ^ "Personal Claim to Top Ten Most Wanted". News Record. March 24, 1994. p. 6. Archived from the original on April 30, 2022. Retrieved April 30, 2022.

- ^ "DreamWorks Press Release". The News Journal. September 9, 2001. p. 174. Archived from the original on April 30, 2022. Retrieved April 30, 2022.

- ^ Sabljak, Mark (1990). Most wanted : a history of the FBI's ten most wanted list. Martin Harry Greenberg. New York: Bonanza Books. ISBN 0-517-69330-5. OCLC 21227684. Archived from the original on July 3, 2020. Retrieved April 30, 2022.

- ^ "Concedes not on most-wanted list". The Guardian. December 19, 2002. p. 36. Archived from the original on June 15, 2022. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ^ "Dinner speaker concedes not on most-wanted list". Journal Gazette. January 3, 2003. p. 4. Archived from the original on June 15, 2022. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ^ "Post-Rehab II: Keeping it real – Newsthinking by Bob Baker". July 19, 2021. Archived from the original on July 19, 2021. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ^ "Abagnale arrested after two days on the lam". Ledger-Enquirer. November 5, 1970. p. 34. Retrieved August 26, 2022.

- ^ Frank Abagnale Jr on 'Catch Me If You Can' – Film 90022, retrieved September 16, 2022

- ^ "Interview with the FBI agent who arrested Frank Abagnale (part 6)". Pretend Podcast. September 13, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ^ "Abagnale claims parole undercover work". The Indianapolis Star. May 2, 2016. p. A6. Archived from the original on April 29, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ Leiva, Javier (August 30, 2022). "Ambush interview with Frank Abagnale". Pretend Radio, Episode 05. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ "Ohio State catches Frank Abagnale for lecture on life, time in FBI". The Lantern. February 26, 2014. Archived from the original on April 29, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ "Walmart Security Chief Criticizes Data Breach Prevention Strategies". ITPro Today: IT News, How-Tos, Trends, Case Studies, Career Tips, More. March 11, 2022. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ "Ambush interview with Frank Abagnale, the con artist behind Catch Me If You Can (part 5)". Pretend Podcast. August 30, 2022. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ Prairie Pulse: Frank Abagnale, archived from the original on April 13, 2022, retrieved April 13, 2022

- ^ "Abagnale claims federal contracts". Reno Gazette-Journal. January 31, 1988. p. 39. Archived from the original on April 29, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ "Abagnale, Wife File Chapter 7 Bankruptcy". Tulsa World. September 26, 1991. p. 25. Archived from the original on December 13, 2022. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- ^ "Clipped From Kenosha News". Kenosha News. February 26, 1982. p. 7. Archived from the original on June 15, 2022. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ "Clipped From The Atlanta Constitution". The Atlanta Constitution. January 13, 2003. p. C2. Archived from the original on April 29, 2022. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ "Abagnale gave occasional lectures". Newsday. December 23, 2002. p. 72. Archived from the original on April 29, 2022. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ Frank Abagnale Jr: Inside OSU With Burns Hargis, archived from the original on July 22, 2022, retrieved July 22, 2022

- ^ The FBI : a centennial history, 1908–2008. [Washington, D.C.]: U.S. Dept. of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2008. ISBN 978-0-16-080954-5. OCLC 263538116.

- ^ Katz, Michael (July 25, 2019). "Frank Abagnale, inspiration for Catch Me if You Can, in Boise". Idaho Statesman. pp. 16–21. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ^ "Most wanted: FBI seeks more applicants for special agents". wtsp.com. February 25, 2019. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ "Abagnale Claims to be Ethics Instructor at FBI Academy". Star Tribune. May 13, 2015. p. D2. Archived from the original on April 29, 2022. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ "Google collaborates with news industry to combat misinformation". International News Media Association (INMA). Archived from the original on November 16, 2022. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ^ "We caught him because we could: Frank Abagnale Jr. still conning us", Scams & Cons, retrieved November 28, 2023

- ^ "Xavier University". Xavier University. Archived from the original on October 11, 2022. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- ^ a b "Conman speaker under fire, now leaving college circuit". Ledger-Enquirer. October 21, 1982. p. 2. Archived from the original on November 16, 2022. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ^ "Con Man Speaker Under Fire, Now Leaving College Circuit". Ledger-Enquirer. October 21, 1982. p. 1. Archived from the original on November 16, 2022. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ^ Hunt, Stephanie (September 2010). "Charleston Profile: Bona Fide". Charleston Mag via abagnale.com. Archived from the original on October 6, 2010. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ^ Stenning, Paul (2013). Success – By Those Who've Made It. In Flight Books. p. 102. ISBN 978-1628475869.

External links

[edit]- Living people

- 1948 births

- 20th-century American businesspeople

- 20th-century American criminals

- American businesspeople convicted of crimes

- American confidence tricksters

- American male criminals

- American people convicted of fraud

- American people imprisoned abroad

- American people of Algerian descent

- American people of French descent

- American people of Italian descent

- American white-collar criminals

- Businesspeople from New York City

- Businesspeople from Tulsa, Oklahoma

- Criminals from the Bronx

- Escapees from United States federal government detention

- Foreign nationals imprisoned in France

- Forgers

- Impostors

- Military personnel from New York (state)

- Prisoners and detainees of Sweden

- Prisoners and detainees of the United States federal government

- United States Navy personnel of the Vietnam War